Genetically modified monkey could be key to curing some diseases

|

||||

| In this story: Modifying a monkey Animal rights concerns Next step -- humans? RELATED STORIES, SITES

|

(CNN) -- A genetically modified monkey could be the key to one day curing a number of human diseases, researchers said Thursday.

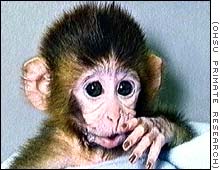

The baby rhesus monkey -- named ANDi, for "inserted DNA" spelled backwards -- carries in him an extra bit of DNA from a jellyfish. Although mice have been altered in this way for years, ANDi is the first primate to be similarly modified.

Researchers at the Oregon Regional Primate Research Center said their technique could eventually be used to insert a human disease gene into a monkey, creating a better way of studying diseases like Alzheimer's, diabetes and breast cancer. The center is part of the Oregon Health Sciences University.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"In order to eradicate these diseases we need to have the relevant disease models to perfect these innovative cures and make sure they are safe and optimized before testing them on patients," said Dr. Gerald Schatten, who led the research at the primate center.

Because monkeys are genetically closer to humans than mice, they could give scientists a better understanding of how diseases develop in people.

The research was described in Friday's issue of the journal Science.

Modifying a monkey

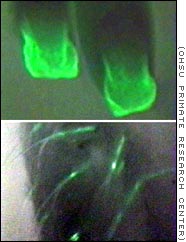

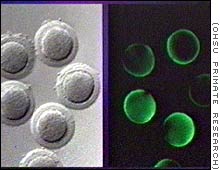

To create ANDi, Schatten and his team injected the jellyfish gene for green florescence into the unfertilized egg of a normal female rhesus monkey. The jellyfish DNA joined with the monkey DNA. The egg was then fertilized with sperm from a normal male monkey.

Three monkeys were successfully altered in this way, but only ANDi survived.

The jellyfish gene was used, Schatten said, because it is known to be harmless and because it is easily detectable.

|

||||

ANDi appears normal so far - he does not glow the way a jellyfish does. But the two other monkeys who got the gene did exhibit florescence. Their hair and fingernails glowed green when exposed to ultraviolet light under a microscope.

Eventually, Schatten said, scientists hope to insert other types of harmless genetic markers that can be tracked with magnetic resonance or PET scans. If successful, doctors might be able to monitor the developmental events that lead to many diseases, he added.

Animal rights concerns

"Meddling with the building blocks of life is extremely dangerous," said Peter Wood, a spokesman for People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. "It goes right to the core of the research philosophy, which is 'I can do with animals as I please. I can even change their physiology.'"

Wood also said he doubted the work would yield new discoveries to treat human diseases.

Animal rights activists were critical of the new research.

But Dr. John Strandberg, director of comparative medicine at the National Institutes of Health, disagreed. He said monkeys could prove to be very useful in studying human diseases.

"The genetically modified animals in the lab have been principally mice, which are good but far removed from humans. How relevant their results are to humans is questionable," he said. "The closer you can get to the human situation, the more accurate are the results you get."

|

||||

Next step -- humans?

So now that scientists have put a jellyfish gene into a monkey, do they now want to insert a gene from a non-human animal into a human being?

No, said Schatten. "We don't support any extension or extrapolation of this work from laboratory animals to humans."

Several scientists and ethicists interviewed by CNN said they don't know of anyone who's interested in inserting animal genes into humans because it could be risky and has no known medical use.

But bioethicist Art Caplan at the University of Pennsylvania said even though no one's interested now, the work with ANDi is a "baby step to genetically engineering ourselves, but we still have a long way to go.

"The time for the public to discuss the ethics of genetic engineering is now, even though we're just at the start of the genetic trail," he added.

CNN Medical Correspondent Elizabeth Cohen contributed to this report.

![]()

Genome the crowning achievement of medicine in 2000

December 31, 2000

Gene research yields drug that helps heal chronic ulcers, company announces

September 13, 2000

U.S., Britain urge free access to human genome data

March 14, 2000

![]()

Oregon Regional Primate Research Center Home Page

Oregon Health Sciences University

Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine

National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)

The Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Organization

Note: Pages will open in a new browser windowExternal sites are not endorsed by CNN Interactive.

![]()